Description |

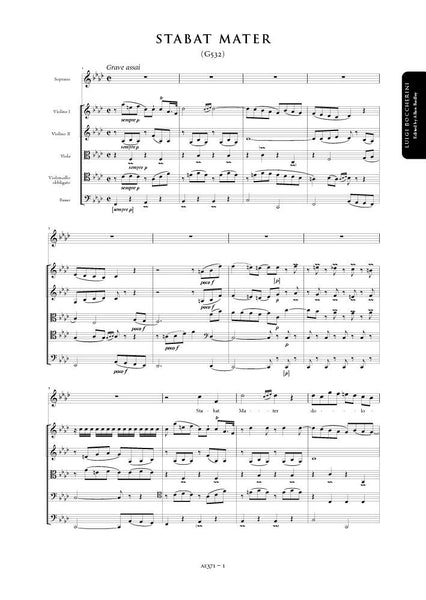

Boccherini, Luigi (1743-1805)

|

||||||||||||||||||

Details |

Boccherini's professional circumstances dictated that his main occupation would be the composition of chamber music. Nonetheless, the Stabat Mater of 1781 is one of the great masterpieces of 18th-century scared music whatever standards one cares to measure the work by. It is strikingly original in conception, uniformly brilliant in its composition and intensely personal in tone. The intimacy of the setting - solo soprano and string quintet - not only suits Boccherini's strongly idiosyncratic musical style but also allows him to depict Mary's grief with such conviction and psychological depth as to make larger-scale settings seem somehow remote and uninvolved by comparison. Boccherini's Mary is not only the grieving Mother of Christ but, of course, symbolic all mothers and all of Mankind. Nothing is known of the work's genesis beyond the fact that Boccherini composed it in 1781 presumably for a singer who was resident at the Infante's court for some time. The vocal writing is so exquisite that it is hard to imagine that Boccherini could have composed it without having had an opportunity to study the singer's voice in great detail.Who this singer might have been we have no idea. However, on the basis of the work written for her - or conceivably for him - she was an artist of rare musical ability. Boccherini's decision to rework the Stabat Mater in the last years of his life may have been due to a number of factors, not least among them, the recognition that the original setting required a singer of extraordinary ability and stamina to perform the work as it was conceived. Given the enormous amount of sacred music composed during the 18th century there are comparatively few settings of the Stabat Mater . This is perhaps not surprising given the rather chequered history of the text and its limited liturgical use. Once attributed to Jacapone da Todi (d 1306), the Stabat Mater is now generally considered to be of 13thcentury Franciscan origin. The text was probably not intended as a sequence for the Mass although it shares the same verse form with the later metrical sequence. The Stabat Mater came into use as a sequence in the late 15th century in connection with the new Mass of the Compassion of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was removed from the liturgy by the Council of Trent (1543-63) but was revived by Pope Benedict XIII in 1727 for use on the Feast of the Seven Dolours (15 September). Outside Rome the sequence was sometimes set for solo voice only with instrumental accompaniment. Elsewhere the Stabat Mater did not really engage the attention of composers. Mozart's early setting (K33c, 1766) is lost and Haydn's, while interesting, has never been regarded as one of his great sacred works and performances of it are comparatively rare. Of his major Viennese contemporaries,Wanhal is known to have set the text once (1782) and Leopold Hofmann, Kapellmeister at St Stephen's Cathedral, and the leading church musician in the city, does not appear to have set it text at all. Given the limited performance opportunities for the Stabat Mater we can be reasonably confident that Boccherini's setting was written at the express request of Don Luis - or, at the very least, its composition must have been approved by him - and performed for the first time on 15 September 1781. The present edition is based on Boccherini's own MS parts which are preserved in the Library of Congress, Washington DC, under the signature M 2103.3 B65 case. The most complete title details are given on the front cover of the Basso part: Ano de 1781 / Basso / Stabat, Mater / a Solo / Con Viols. Viola, e Violon, obligado / Del Sigr dn Luigi Boccherini . Each part concludes with his customary Laus Deo. Boccherini's markings are for the most part unambiguou although there are naturally instances where he omits markings or simply miscopies from the autograph score. There are few if any corrections in the parts and doubtless minor details would have been agreed in rehearsal. The composer's orthography is delightfully inconsistent and appears at times to hint at a certain confusion on his part as to whether he is an Italian or a Spaniard. The instrumental writing contains a wealth of detail and there is little in the music which is purely functional. The myriad subtleties of instrumental texture, the wonderful interplay of the six parts and the high level of melodic invention are the work of a great artist. Boccherini himself probably played in the premiere of the work and it is tempting to assign special significance to the one movement which has an important cello solo, Eja Mater , fons amoris, surely one of the most beautiful movements written in the late 18th century. In preparing this edition the style and notation of Boccherini's articulation and dynamic markings have been standardised throughout, and, where missing from the parts, markings have been reconstructed from parallel passages. Boccherini's Latin punctuation is a little erratic and his spelling at times is inconsistent. These have been corrected in the edition although Boccherini's text underlay has been retained throughout as this has an obvious bearing on the performance of the work. Obvious wrong notes have been corrected without comment; editorial emendations with no authority from the source are placed within brackets. Allan Badley |

Loading...

Error

![Hofmann, Leopold: Missa in D (Badley C13b) [Vocal Score] (AE624/VS)](http://www.artaria.com/cdn/shop/files/ae624vs_1stpage_large.jpg?v=1697794050)

![Hofmann, Leopold: Missa Sancti Aloysii (Badley D8) [Vocal Score] (AE409/VS)](http://www.artaria.com/cdn/shop/products/AE409_VS_Inside_1_large.jpg?v=1571438578)

![Hofmann, Leopold: Missa Sancti Erasmi (Badley D4a) [Vocal Score] (AE642/VS)](http://www.artaria.com/cdn/shop/files/ae642vs_1stpage_large.jpg?v=1697798128)