Description |

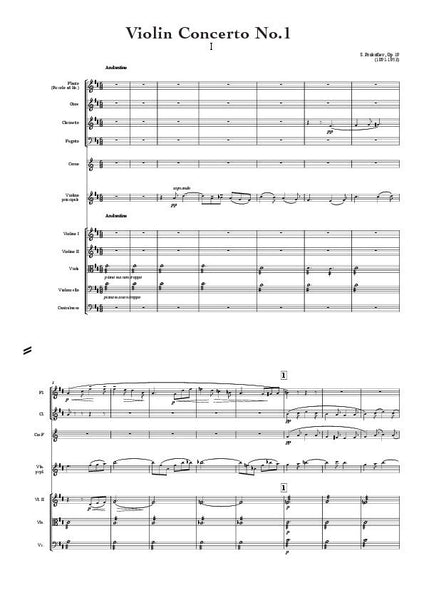

Prokofiev, Sergei (1891-1953)

|

||||||||||||||||

Details |

Artaria Editions is very pleased to introduce a new concept to the study and performance of standard repertoire concertos. Arranged for soloist and chamber ensemble, typically consisting of a quintet of wind players and a string quintet, these new arrangements provide soloists with an opportunity to rehearse and perform major repertoire under conditions closely resembling a full orchestral setting. They provide valuable practice for small ensembles to work with soloists and an ideal vehicle for student conductors to work with major solo repertoire. Sergey Prokofiev was born in 1891 at Sontsovka in the Ukraine, the son of a prosperous estate manager. An only child, his musical talents were fostered by his mother, a cultured amateur pianist, and he tried his hand at composition the age of five, later being tutored at home by the composer Glière. In 1904, on the advice of Glazunov, his parents allowed him to enter the St Petersburg Conservatory, where he continued his studies as a pianist and as a composer until 1914, owing more to the influence of senior fellow students Asafyev and Myaskovsky than to the older generation of teachers, represented by Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov. Even as a student Prokofiev had begun to make his mark as a composer, arousing enthusiasm and hostility in equal measure, and inducing Glazunov, now director of the Conservatory, to walk out of a performance of The Scythian Suite, fearing for his sense of hearing. During the war he gained exemption from military service by enrolling as an organ student and after the Revolution was given permission to travel abroad, at first to America, taking with him the scores of The Scythian Suite, arranged from a ballet originally commissioned by Dyagilev, the Classical Symphony and his first Violin Concerto. Unlike Stravinsky and Rachmaninov, Prokofiev had left Russia with official permission and with the idea of returning home sooner or later. His stay in the United States of America was at first successful. He appeared as a solo pianist and wrote the opera The Love for Three Oranges for the Chicago Opera. By 1920, however, he had begun to find life more difficult and moved to Paris, where he re-established contact with Dyagilev, for whom he revised The Tale of the Buffoon, a ballet successfully mounted in 1921. He spent much of the next sixteen years in France, returning from time to time to Russia, where his music was still acceptable. Twelve years later the name of Prokofiev was to be openly joined with that of Shostakovich in an even more explicit condemnation of formalism, with particular reference now to Prokofiev's opera War and Peace. He died in 1953 on the same day as Joseph Stalin, and thus never benefitted from the subsequent relaxation in official policy to the arts. As a composer Prokofiev was prolific. His operas include the remarkable The Fiery Angel, first performed in its entirety in Paris the year after his death, with ballet-scores in Russia for Romeo and Juliet and Cinderella. The last of his seven symphonies was completed in 1952, the year of his unfinished sixth piano concerto. His piano sonatas form an important addition to the repertoire, in addition to his songs and chamber music, film-scores and much else, some works overtly serving the purposes of the state. In style, his music is often astringent in harmony, but with a characteristically Russian turn of melody and, whatever Shostakovich may have thought of it, a certain idiosyncratic gift for orchestration that gives his instrumental music a particular piquancy. He had begun the concerto two years before, in 1915, envisaging a concertino. This grew into a concerto, and a performance had been planned in 1917 under Alexander Ziloti in Petrograd. The time was inauspicious and the concerto eventually received its first performance in Paris six years later at a concert conducted by Koussevitzky with the violinist Marcel Darrieux, after Hubermann and other distinguished violinists had refused to learn it. Among the members of a distinguished audience that included Szymanowsky, Rubinstein, Picasso and Pavlova, was Joseph Szigeti, who took the concerto into his own repertoire, giving the first performance of the work in what was now Leningrad in 1924 and in his concert tours introducing it to a much wider public. The first movement of the concerto opens meditatively, the soloist entering with a theme marked sognando (dreaming) over a tremolo string background, into which flutes and clarinets are soon added. This is developed, leading to a passage of greater astringency and trills that moves forward to an angular second subject, marked recitando, and a passage of those insistent motor rhythms that are such a feature of Prokofiev's writing. Clarinets and flute suggest the opening of the principal subject, against the plucked notes of the solo violin, before the motor rhythms of the soloist resume, over an orchestral development of the opening figure, increasing in intensity. The music slows to meno mosso and a brief passage of double-stops for the soloist before a muted string tremolo leads to a return of the first theme, played by the flute, with accompanying figuration from the solo violin in the higher register of the instrument. The Scherzo offers an immediate contrast, with its chromatic theme and use of interpolated plucked notes from the soloist. There is a contrasting section, marked by insistent and repeated rhythms, at first played on the G string, sul ponticello (near the bridge) and con tutta forza (as strongly as possible), and then, at its second appearance, muted. The first theme eventually prevails, reintroduced by the flute. The third movement opens ominously enough, with a brief theme for the bassoon, before the soloist's lyrical emergence, over the continued rhythm of the orchestra. The soloist takes up an ostinato rhythm, resumed, before a change of mood, a reminiscence of the feeling of the opening of the concerto in its treatment of the principal theme of the movement. After another episode of increasing tension, the opening theme of the first movement now returns to close the concerto with the gentle lyricism of its beginning. |

Loading...

Error